Imagine stepping into a bustling farmers market, brimming with colorful stalls overflowing with fresh produce. You’re a farmer, eager to sell your delicious tomatoes, but you’re not the only one. The market is crowded with countless other farmers, each selling their own perfect-looking tomatoes. How do you decide on the price for your tomatoes? And what forces influence how many tomatoes you can sell at that price? This everyday market scenario encapsulates the essence of what we’re about to explore: the demand curve facing a competitive firm.

Image: courses.lumenlearning.com

This article dissects the demand curve faced by a competitive firm, unveiling the crucial factors that determine its shape and how it influences the firm’s pricing and output decisions. We’ll delve into the unique characteristics of perfect competition, how it sets a competitive firm’s demand curve apart, and its implications for the firm’s profitability. By understanding these dynamics, you’ll gain valuable insights into the intricacies of the market and how businesses operate within it.

Perfect Competition: A Level Playing Field

At the heart of understanding the demand curve of a competitive firm lies the concept of perfect competition. It’s a theoretical framework that defines a market structure where numerous firms sell homogeneous goods or services. Here, no firm has the power to influence the market price, acting as a price taker, responding to the market price instead of dictating it. Think of the farmers market again, with many farmers selling indistinguishable tomatoes. One farmer’s pricing strategy doesn’t sway the market price; they simply take the prevailing price set by market forces.

In a perfectly competitive market, several key characteristics come into play:

- Many Buyers and Sellers: A multitude of buyers and sellers ensure that no single participant holds significant power to influence prices.

- Homogeneous Products: Goods and services offered by different firms are identical in the eyes of consumers. Think apples from different farms; they are considered interchangeable.

- Free Entry and Exit: Firms can enter or exit the market without significant barriers, allowing for competition and adjustments based on market conditions.

- Perfect Information: Buyers and sellers have complete knowledge about the market, including prices and product quality, enabling rational decision-making.

This ideal scenario provides a clear foundation for analyzing the demand curve of a competitive firm.

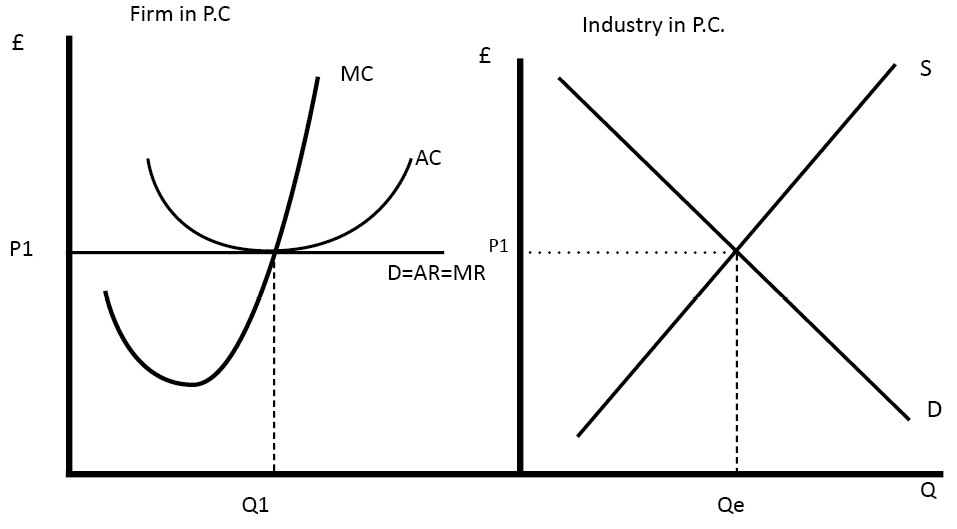

The Perfectly Elastic Demand Curve: A Horizontal Line

In the realm of perfect competition, the demand curve facing a single firm is perfectly elastic. This means that at any given market price, the firm can sell as much or as little as it wants. The demand curve is depicted as a horizontal line, implying that the firm can sell any quantity at the prevailing market price without affecting the price itself. The firm’s output is too small to have a noticeable impact on the market supply, leaving it at the mercy of the market forces that dictate price.

Imagine a farmer at the market. If the prevailing price of tomatoes is $1 per pound, the farmer can sell any quantity at that price. Whether they bring 10 pounds or 100 pounds, they will still sell them at $1 per pound. The market is so large, and the farmer’s contribution to the overall supply so small, that their individual output doesn’t affect the price.

The Magic of Marginal Revenue: Always Equal to Price

In a competitive market, a crucial concept comes into play: marginal revenue. Marginal revenue is the additional revenue a firm receives from selling one more unit of a good. In perfect competition, marginal revenue is always equal to the price. This might sound straightforward, but it has significant implications for the firm’s decision-making.

Since the firm can sell any quantity at the market price, selling one additional unit generates revenue exactly equal to the market price. The firm doesn’t have to lower its price to sell more, so the marginal revenue from selling that extra unit is simply the price itself. This equality between marginal revenue and price is a defining characteristic of perfect competition and plays a crucial role in determining the firm’s optimal level of output.

Image: www.economicshelp.org

Profit Maximization: Where Marginal Cost Meets Marginal Revenue

Every firm, in the pursuit of maximizing its profits, aims to strike the right balance between its costs and revenues. In the case of a competitive firm, finding this optimal output level hinges on the interplay between marginal cost and marginal revenue.

Marginal cost (MC) represents the extra cost incurred by producing one additional unit. Remember, in a perfectly competitive market, marginal revenue is equal to the price (MR = P). So, the profit-maximizing output level for a competitive firm occurs where the marginal cost equals the price, or MC = P.

Think about it: if the marginal cost of producing an additional unit is lower than the price, the firm can increase profits by producing and selling more. Conversely, if the marginal cost exceeds the price, producing one more unit would lead to a loss. At the point where MC = P, the firm has maximized its profit, as producing more or less would reduce its overall profit.

Shutting Down: When Costs Outweigh Revenue

While the goal of any firm is to maximize profits, sometimes the market circumstances force firms to make tough decisions, including temporarily shutting down operations. This decision hinges on the relationship between the firm’s total revenue and its variable costs.

Variable costs are those that change with the level of output. Imagine the farmer’s market again. If the farmer decides to sell tomatoes, they incur variable costs associated with picking, packaging, and transporting their produce. If the market price falls below the farmer’s average variable cost (AVC) per tomato, it means they are not even covering their variable costs. In this situation, the farmer would be better off shutting down temporarily, minimizing their losses.

However, if the price falls temporarily below the AVC but is expected to rebound, the farmer might choose to continue operating in the short run. This decision reflects the fact that the firm still has to cover its fixed costs, even if they are not producing. Fixed costs represent those costs that don’t change with output, such as the cost of renting land or the cost of tools. By operating in the short run, the firm can minimize losses by covering some of its fixed costs, even if they’re not covering all of their variable costs.

The Long-Run Equilibrium: Profit-Maximizing Yet Competitive

In the long run, firms in a perfectly competitive market face a more challenging reality. Since there are no barriers to entry, new firms can enter the market if the existing firms are earning economic profits (profits that exceed the cost of capital). The influx of new firms increases the market supply, driving down the price to a level where only normal profits are possible. Normal profits simply mean that the firm is earning a return on its investments that is equal to the opportunity cost of capital. This means that firms are covering all their costs, including fixed and variable costs, but not earning extra profits.

This long-run equilibrium represents a dynamic where firms, albeit operating under the pressure of intense competition, can still achieve profit maximization based on their individual cost structures. Since the price reflects the minimum average total cost (ATC) of the most efficient firms, those firms that operate with higher costs will eventually be forced to exit the market or find ways to reduce their costs.

Real-World Applications: Finding Perfect Competition

While perfect competition is a theoretical framework, it provides a valuable framework for understanding market dynamics. Although true perfect competition might be rare, certain industries come close to this ideal, such as:

- Agriculture: The agricultural sector often features a large number of farmers producing largely undifferentiated products, such as grains or basic vegetables. Of course, factors like location, brand reputation, and variations in quality can introduce some degree of differentiation.

- Foreign Exchange Markets: Spot markets for currencies, where currencies are traded in real-time, exhibit characteristics of perfect competition due to the large number of buyers and sellers. The rapid trading and price fluctuations reflect the equilibrium-seeking nature of perfect competition.

- Online Marketplaces: Marketplaces like Amazon or Etsy with numerous sellers offering similar products, especially in categories like books or handcrafted goods, often exhibit characteristics of near-perfect competition.

2 The Demand Curve Facing A Competitive Firm

Conclusion: A Framework for Understanding Market Dynamics

The demand curve facing a competitive firm, shaped by the forces of perfect competition, offers a valuable framework for understanding how businesses operate in a market where they have minimal power to influence prices. This article has examined the interplay of key concepts like marginal cost, marginal revenue, and price, shedding light on how firms in this environment strive to maximize profits while navigating the dynamics of competition. Although perfect competition might be a theoretical construct, it provides a fundamental foundation for understanding markets, whether they involve farmers at a bustling market or global currency exchanges.

As you engage in the world of business, understanding the demand curve and its implications will equip you with the knowledge to make informed decisions and navigate the competitive landscape, just like those farmers at the market, seeking to sell their tomatoes at the best possible price and maximize their profits.